#67: The work behind the work of chasing career-defining projects

Understanding the ripple effect of great projects and more

Dear friends,

It’s was a long weekend for some of us the United States. I am grateful for any bit of extra time back.

I spend a lot of time thinking about careers and how it shapes people’s lives. In my case, I know it definitely is influencing a lot of my own life. What I wrote today is a retrospective of just some of my best work. The initial goal is to analyze what makes a project great and how would that define a person’s career using my own work as a case study.

This whole process reminded me so much of this famous quote from Steve Jobs: “You can't connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards. So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future. You have to trust in something—your gut, destiny, life, karma, whatever. This approach has never let me down, and it has made all the difference in my life.”

I count my lucky stars whenever I look back at all the work I’ve done my whole life. Not necessarily because a lot of them were extraordinary or even world-changing, not even close. It’s because they did change the trajectory of my life, in one way, or another.

Truthfully, I still question a lot of it. I’ve lost track of the number of times I had to ask myself the following questions:

How did I end up doing this?

Was it always a given? Maybe.

What are the multitude of things that has to happen before a BIG thing happens?

Can I recreate this over and over again?

Do I even want to? Wouldn’t that be counterproductive in this business of creativity and innovation?

How can I ensure that my stamina can keep up with my ambitions? my ambitions with the uncertainties that come with this industry?

Although I am a big fan of questions, I don’t want them to remain as such. There’s a reason why things happen (or don’t happen). Maybe it’s luck, maybe it’s just good timing. But most of the time, those are not enough.

One not only has to be prepared for these good things to happen—but should also expect them to, and most importantly, act as if it’s already done. From my vast readings on these subjects (‘exceptional people’, ‘careers’, ‘business of creativity’ etc) and, of course, from my own personal observations, this is a known pattern/framework or mental model, whatever you want to call it. This is also one of the hardest things to do for it requires a lifetime of commitment to self-growth and self-development.

There is no shortcut to landing great work. In a lot of ways, it is a path that reeks of privilege. Gifts sometimes feel like privilege, the line is oftentimes blurred. To distinguish one thing over the other is probably pointless, if you have it. The better thing to do is to know how to use it and use it well.

As designers, we have that gift and privilege. Too much, sometimes, even. It becomes a problem if these two things are true:

We don’t know how to use it and use it well - when the situation calls for it

We are unaware of the consequences of it - bigger issue?

But I am not going to go into this, as tempting as it is. Instead, my post for today is for the complete opposite scenario: When you’ve done a pattern of amazing work, how do you leverage it? How do you get more of it?

I know I talk a lot about the ‘work that matters’ here on this platform and elsewhere. It’s kind of like a north star, really, to a lot of what I do. Obviously, the financial rewards are great. But there’s one aspect of this that I want to explore today, to be honest, as it is not talked about nearly enough: Learnings.

I’ve reflected a lot on the projects I’ve done that consider to be great. In this essay, I’m happy to share those lessons in the form of patterns I’ve uncovered. This is probably not the full extent of this but here’s what I have so far.

Great projects aren’t always obvious.

I was already a mid-level designer when I found myself working on—what I would later call—my first big, high-visibility project. At that time, I had no idea of the significance of it, not just to my portfolio, but also to the trajectory of my career later on. As with most things of this nature are, you rarely ever feel a good thing if you are in the midst of it.

I just wanted to not screw up. The stakes were enormous after all. I still remember that day I got to present a conceptual deck of it in front of the clients and a few of my colleagues. I had mild panic attack in the office just an hour before we went into that conference room. It wasn’t the best of times, mentally and emotionally but boy, I remember thinking to myself: I just landed my first whale, my first real baby.

That foreign feeling stuck with me for so long, it became a driver to a lot of what I do. I want nothing more than to feel that feeling, all the time. At all times. It makes all of the hard work and sacrifices worth it. It gave me pride, a whole lot of it.

It was a high I kept chasing since then.

Great projects have a ripple effect into the future.

Just for some bit of transparency, the project from above was a collaboration between by agency at that time and two of the biggest companies in asia, Globe Telecom and Disney Asia. It was this giant, heavily-funded, cross-platform (digital/traditional), international campaign for this little film called Star Wars: Episode VII - The Force Awakens (2015). I thought this context is significant. I mean, just how often can one say they’ve been a part—a tiny part—of something like this?

I was one of the lead interaction designers on the digital side and it was a crazy time in my professional (and personal) life, no doubt. I can’t tell exactly when I’ve realized just how valuable of an opportunity and asset this was to my portfolio. I didn’t fully realized this until I moved to the States months afterwards.

It was 2016—I had nothing but a suitcase, and an ipad to showcase my work. Money was extremely tight. I had to find a job as soon as possible. The portfolio i’ve clumsily put together probably wasn’t the best, in retrospect. In fact, I’ve thrown away 90% of it except for one piece.

This was the only project that caught the interest of the recruiters, hiring managers and eventually, my future bosses and colleagues. One time, an interview went really well that the hiring manager had to take photos of that particular slide to show to her boss, who ended up being one of my first bosses in new york city.

This story, no matter how many times I tell it, will never get old. I’ve learned a lot, obviously. But the one thing is pretty clear, after all of this: rarely do we ever get to contribute to something that will make a real dent to our future prospects in life. Especially with a lot of white-collar work, it always feel like we’re just a cog in a system that so often benefits the top. If there’s even a slight chance that the pendulum swings the opposite, grab it. Take it. Squeeze it for all of its worth…ethically.

We are given what we are given because of a huge number of factors: time, luck, connections, pedigree, work ethic. For all the data points that we can control, go above expectations, as often as you can, as wide or as deep as you can. I firmly believe these are previews to our destiny as _whatever we see ourselves at_.

There’s a lot of clues to our future and they’re all scattered in the present, if one looks closely. In terms of work, this is very much true. Don’t wait for great things to land on your desk. Set yourself up so that when they do come, you are more than ready. Never take for granted what you have. It’s only as useful as you make it to be.

Great projects result to great learnings.

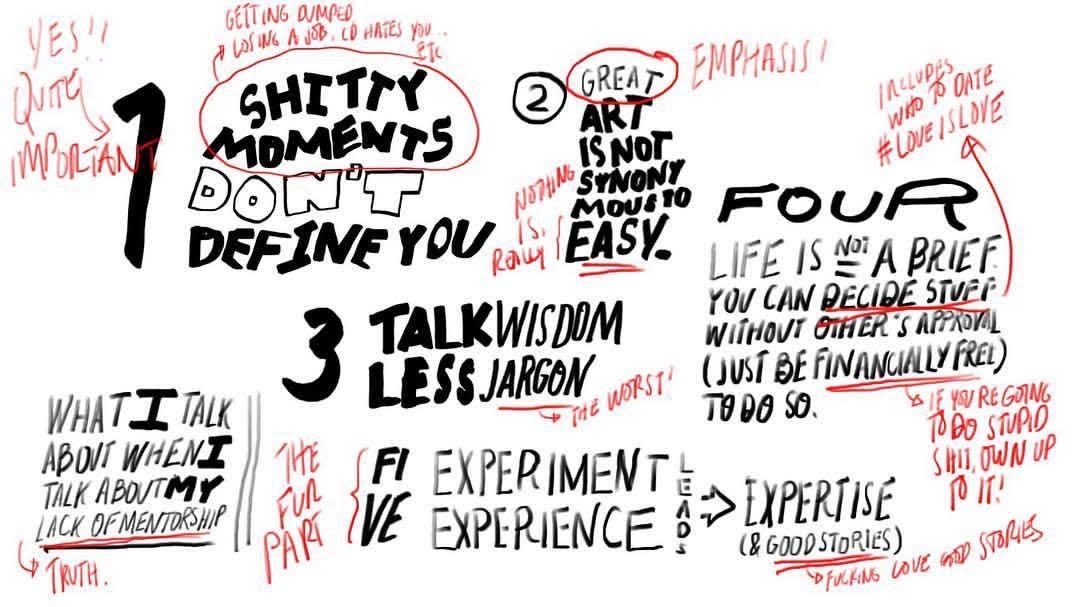

Fast forward to 2021, for my first ever talk, I told this story of how I mapped out the user journey of my career. I pitched the idea and wrote a short brief about it, got selected and eventually coached by the organizers. They were really valuable in the process of turning an idea into a solid, storytelling-driven presentation.

I was never really good at public speaking. However, I took that opportunity to change that, or at least try to stir it into a better direction. It was a personal challenge, and I was willing to fail in the attempt.

Thankfully, I didn’t. I thought it was a decent experience, one that certainly gave me a new perspective and a ton of insights I’m still personally using up to this day.

The bread-and-butter of that talk is this summary of the best things I’ve ever learned from my career, at that point in time. My personal favorite of which is this: Experiments and experiences lead to expertise (& good stories!). This is true for the talk as it is for great projects. It is even true for a lot of what we pursue on our personal lives, to some degree.

A great project doesn’t end when the product gets shipped and the customers get ahold of it. It doesn’t end when the work gets refactored and there’s a 2.0 on the horizon. It doesn’t even end long after you leave the team or the company. A great project ends when you’ve finally learned the lessons from it.

You learn the lessons enough to carry it with you unto the next one, and you start to let go of the old ones. In order for new things to come in, certain things have to go.

But the hallmark of a great project is even in the act of letting go, it gives you back something that is extremely priceless: lifelong lessons through war stories, anecdotes and shared memories with people you’ve put out fires with. They’re not all happy stories, for sure. That is not the point of a great project.

The point of a great project is to learn how to fight the worthy battles, choose the people to fight those battles with and try your hardest to win them. Winning, in this case, could mean a variety of things:

Designing a really spectacular experience for the right type of users

Solving a critical problem using creativity

Being innovative in your company / industry

Pursuing worthwhile causes that brings in a lot of impact to society

Etc

There’s probably no shortage of lessons that come from great projects. If you are already learning loads from a current project, there’s a chance that you are in the middle of a great one.

Don’t forget to take down notes. You won’t regret them later on.

A few other things that great projects tend to have:

They tend to be multidisciplinary - You are forced to flex and use your underdeveloped creative muscles in the best ways possible. This was evident during the time when I first started learning Python. I shipped a beta version of a product that I designed & coded myself, a totally different experience compared to just being on the design side or just on the coding side.

They tend to attract likeminded but immensely diverse teammates - Working with this hardware startup called Looking Glass Factory for a few years was a testament to this for me. I collaborated with the most creative of folks in new york city and elsewhere: game developers, hardware designers and engineers, artists. It was such a colorful and experimental time in my career and I treasure that deeply. Proud of the work we’ve done together.

They tend to come from ideas that are extremely persistent and resilient

They tend to live on the edges and intersections of the idea-maker’s passions and interests, oftentimes two unrelated things even

They tend to sound crazy at first or silly and unconventional - For a lot of makers/designers/builders, fun is a given, it is hard to go anywhere far without it. Nothing is more daunting than starting from the point of boring, especially with creative work that sparks innovation.

They tend to bear great writing, alongside the actual product - Paul Graham comes to mind with this, alongside Julie Zhou, Sam Altman, Laura Klein, Scott Belsky, Erika Hall and many other people in tech/design who are excellent in both writing and building products.

Great projects don’t have to be flashy or sexy or cool. They don’t necessarily have to be well-funded or award-winning (although that’s nice too). They don’t even have to have the best, most popular people in the team.

Great projects are what you make it, it’s a possibility in every project started with good intentions and creativity. It is up to the makers to make that happen, everything else comes secondary.

Even if a project does not end up to be as great as the makers want them to be, that doesn’t mean it was a failure or the attempt was fruitless. I would argue, there has to be more of that in a maker’s portfolio than the opposite. Simply because that’s where the lessons are and from experience, pain and chips-on-shoulders tend to be a wildly effective driver to change. You can’t get that if you are winning all the time, most especially if all you’ve ever known is the winning team.

You can only get that through experience. Build enough things in your lifetime and you’re bound to land a great project, or two or three, or thousands. The magic is in the act of doing without losing this childlike persona that fuels that intrinsic motivation.

That’s where the transformation happens, for the maker, the maker’s life and the maker’s portfolio.

I’ll say this again: how lucky are we all to do this for a living?

Extremely lucky, if you ask me.

Thank you for reading this essay,

Nikki

PS: This topic is so great, I’m sure there will be a part 2. Keep an eye out for it!

I spoke with a fellow designer a few weeks ago. We had a lovely and productive conversation about the future, the current economy as well as the state of UX, in general. In fact, it went so well, I just had to write down a surprise insight from one of the questions she asked me. Here’s a short transcript, a snippet of that conversation:

On investing in your own career, in your own professional growth:

My answer: Go all in. It’s a lot but it will pay for itself in the near future.

What would you do, knowing what you know now, in order to break into the design industry?

My answer: I would just make things. Ignore labels, all the noise, what I should and what I shouldn’t do based on the job titles I want, just make. Use and explore the variety of tools out there— low-code, no-code, specifically. Anything just to bring an idea—many ideas—out there. That’s how you learn, that’s how you find out what you actually want vs what you don’t want.

Then when you get an idea or two of what you don’t want to do, that’s where things start to become a lot clearer for you. At least it was for me.

It’s hard to start from a place of want— I wanted a lot of things. If you start from the complete opposite, it’s easier to narrow down the paths that are mostly compatible to you and your desired futures. Learned this the hard way.

I always leave my inbox open for these kinds of conversations. If you are interested in connecting, send me a message: nikkiespartinez@gmail.com

Links:

Was this forwarded to you? If you enjoyed this piece of writing, please consider subscribing to my newsletter, Working Title.